Published: 19 Feb 2019

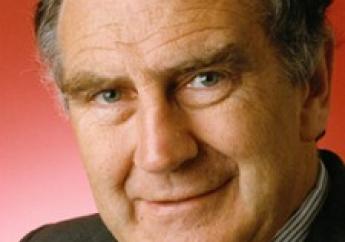

11 July 1934 - 9 February 2019

Senator for Victoria 1985-2002

Barney Cooney will be remembered as a great defender of the union movement and advocate of workers’ rights; as a great champion of the role of the Senate and its committee system; and as a prominent member of the generation of Labor politicians who cast off the legacy of the 1950s Split and prepared the way for the party’s return to power in the state and nationally.

In some people’s eyes, it was ironic that Barney was a staunch member of the Socialist Left. He upheld Labor values while being deeply religious. He was never afraid to defend those who were ostracised or on the margins of society.

The golden thread of his political work was his commitment to social justice and the defence of working people. That is why he was widely respected across the Labor movement. He upheld Labor values while being deeply religious.

He was grievously ill for a very long time, but while his body deteriorated his mind did not. He remained politically active till the very end. He was a member of the Trades Halls Council and the Literary Institute committee of management and attended meetings as late as 28 January this year.

Barney was born on King Island, Tasmania, where his father – also named Bernard – was the branch manager for the Commercial Bank of Australia.

The family’s Irish forbears had connections to Tasmania dating back to the 1820s, but in 1937 the bank transferred Bernard to Culgoa, in the Mallee district of western Victoria.

In the wake of the Depression, there were still many men carrying swags on the roads of the Mallee, who often visited the family home asking for food. If the attitudes held in later life are learned first as a child, the origins of Barney’s politics may be found in that experience. He later said that the courtesy and kindness shown to the itinerant men by his mother, Corrie, formed a lasting impression on him.

The family later moved to the city, where they ran a milk bar in South Melbourne. Barney’s father died in 1951, but Corrie kept up the business until her death in 1968. Barney attended St Kevin’s College from 1947 to 1952 and won a Commonwealth scholarship that allowed him to study arts/law at the University of Melbourne.

He represented the university in boxing, did his national service in the university regiment, and was active in the ALP Club and the Newman Society. Because of the sectarian overtones of the ALP-DLP Split, Catholics were often regarded with suspicion in the Labour movement in Victoria during the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Those like Arthur Calwell, who remained in the ALP rather than leaving to join the DLP, often endured hostility within the church as well. Barney, for his part, always rejected the views of people, whether in the church or the party, who suggested that there was conflict between his faith and his politics.

Throughout his life, he remained a staunch Catholic as well as a loyal member of the ALP. Barney was admitted to the Victorian Bar in 1961 and worked mainly on industrial law and personal injury cases. He chaired an inquiry into workers’ compensation that resulted in the reform of Victoria’s compensation laws. He remained on the Bar roll throughout his political career and after his retirement continued to do pro bono work.

Within the Victorian ALP Barney was originally a member of a group called the Participants, which became the Independents faction after intervention in the Victorian branch by the ALP Federal Executive in 1970.

The Independents, who held the balance between left and right factions in the ‘70s, included many who were associated with Labor’s return to power in the 1980s: John Button, John Cain, Michael Duffy and Richard McGarvie.

Barney was elected to the ALP State Administrative committee as an Independent but did not remain with the faction: he joined the Socialist Left in 1994. By then he was already a member of the Senate, having been elected in 1985 as no.3 on the Labor ticket. He had been preselected with the support of the Socialist Left. At the time of his election, he was 50, and he came equipped with more than 20 years experience in resolving workers’ legal problems.

In his first speech, Barney turned Lord Acton’s famous dictum “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” on its head: if power corrupts, he said, “lack of power corrodes absolutely”. Those in Australia who lacked power “to give at least minimum expression to their needs” included indigenous people, the unemployed and non-English-speaking migrants, especially women. “The more they can be effectively equipped with power”, Barney said, “the more likely it is that their social distress will be abated and the community as a whole benefit”.

From that fundamental commitment, he never wavered throughout his 17 years in the Senate, which he regarded as the chamber best equipped to check abuses of power, chiefly because of its committee system. He chaired seven Senate committees but is perhaps best remembered as an outstanding chair of the Scrutiny of Bills Committee. That committee’s first term of reference – to guard against legislation which would trespass unduly on personal rights and liberties – reflected his own deepest instincts.

Barney was not afraid to criticise his party when he felt it had trespassed in this way. In Caucus he opposed the Hawke Government’s proposed national identity card, which he described publicly as an Orwellian measure. Why should you need a licence to be a citizen, he asked? During his final years in the Senate, Barney was greatly disturbed by an increase in legislation under the Howard Government, particularly on asylum seekers and on measures against terrorism that he regarded as curbing the rights of the individual.

Speaking on various anti-terrorism measures, he said: “What happens with legislation is that it creeps. You cannot look at legislation simply in terms of what is happening now; you have to look at what might happen later on. Once you proscribe an organisation, people say ‘that’s how things are done’. What was put in as an exception originally becomes the precedent for more and more power to be given to the executive, and that is a real problem”.

Barney was held in esteem on both sides of the chamber and on the cross benches because of the courtesy he displayed both in expressing his own views and in responding to criticism by others. “Courtesy and grace are forever needed in debate”, he wrote. “A civil society cannot be at it's best unless constituents treat each other civilly”.

That courtesy was shown to him in the valedictories on his final day in the Senate. Greens leader Bob Brown described him as “a pillar of humanitarianism in the Senate, in the Parliament, where politics is often cool and crude and distancing and cold. In fact he’s a centre of warmth — Barney’s like a little radiator going down the cold corridors of power. The Liberals’ Senator Robert Hill said: “Barney sets the standard to which most of use seek to aspire but rarely reach, in terms of his personal demeanour, his commitment and his values … he is always fighting for the underdog”.

Barney never ceased to fight for the underdog, long after his retirement from the Senate. He continued to represent unions in legal disputes right up until his final illness and was always generous with his time when others sought his advice or assistance. He was a mentor to many Labor politicians and union officials, and Australian public life was enormously enriched by Barney Cooney’s contributions to it. We are all in his debt.

He is survived by his wife, Lillian, and four of their five children.

- Senator Kim Carr

Members are respectfully invited to attend a funeral service for Barney, which will be held on Friday 22 February at St Ignatius Catholic Church, Richmond at 1.30pm.